Where I peer through half-closed eyes at mountain vistas

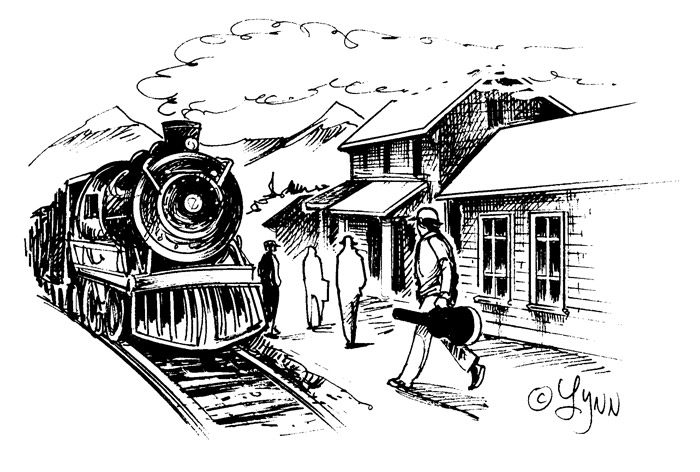

B.C. August, 1977. After the hubbub had settled down, I prepared to resume my trip; this time by rail, bus and ferry.

The train line that ran by my digs in West Vancouver had a history. The Pacific Great Eastern ran from the Vancouver’s North Shore up through what is now the Whistler corridor, past Anderson and Seton lakes, through Lillooet and into the Cariboo. In the old days, the locomotives were steam. One of those famous engines was the Royal Hudson. In the seventies, they reconditioned this old beauty and put her back in service. Every morning, at 8.30, it would steam by my house as it hauled tourists to Squamish. It was a sight. This was the train I took on the first leg of my journey north. The trip is spectacular, and seeing the land from an open vestibule on the back of a train is even better.

At Prince Rupert I caught the Alaska ferry north, roughly following the route I had taken in 1965. Then in Skagway, twelve years after my first visit, I finally got to climb the iron steps onto one of those old White Pass train cars that would trans- port me to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory.

•••

Every journey has a soul. Gut feelings about an upcoming adventure can run the gamut from, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ to, ‘This is written in the stars.’ The moment I climbed on that train to head over the pass, I knew it was all meant to be.

Pulling out of the station in Skagway, you click-clack north on the valley floor, then you start to climb – fast. In fact, within 10 miles as the crow flies, you go from sea level to 3300 feet. Jagged peaks separated by glaciers surround you as you climb above treeline and into a moonscape of rock that looks like it was transplanted from the barren lands of the Arctic coast.

Then you descend a little, dropping into the welcoming landscape of Northern B.C. and the Yukon. The coastal, wet weather gives way to a drier, friendlier environment where pine, spruce and poplar line deep blue lakes. The air is softer, the breezes lighter, and the colours more pastel.

The engine throbbed, the cars swayed, and the wheels clattered as we slid through that majestic landscape. I just sat and stared at the spectacle through the windows of the old railway car, mesmerized. And it didn’t let up. After Jamie picked me up in Whitehorse, we drove the final 60 miles down the Atlin Road, turned the final corner into the town, and bingo! – there it was – Atlin Mountain rearing up out of an eighty mile long, glacier fed lake. I was gobsmacked.

Atlin is on what they call the ‘Southern Lakes.’ That, of course is relative, straddling as they do, the Yukon border. These are big bodies of water that are the headwaters for the Yukon River. Most of them lie tucked into the coast mountains, and many have glaciers flowing into them from the south and west.

My visit there was a series of firsts – first time in the Yukon, first time in a small aircraft (a little Cessna 172 on floats), first time on a sheep hunt, (entirely unsuccessful), and the first time I truly felt that anything was possible.

I was sitting on the back porch of Jamie Stephen’s house one evening, looking out over a startlingly blue Atlin lake. It was fall, and the poplars had turned brilliant yellow. They shimmered in a light breeze. Peering down Torres channel, I could see the outline of Cathedral mountain and a tongue of the Juneau Icefield drop- ping into the lake from the Coast Mountains. I felt like I had ingested some sort of hallucinogen. Wherever my eyes turned, they were assailed by indescribable beauty. Then the most peculiar of things happened.

The residents had been complaining recently about open range horses in the area. The local outfitters were in the habit of letting them loose when they weren’t in service, and they often ended up poking around town and making nuisances of themselves. One in particular, we’ll call him Andy for the purpose of this tale, had wandered through the trees, sneaked towards the porch and was now in the process of trying to stick his head through the top two beams of the back porch fence.

It was a big old head, so it wasn’t an easy task, but he seemed determined. Finally, job done, he directed a pair of mischievous eyes at me, shook his mane, and snickered,

“Roll up your sleeves pal. This is the spot.” I stared back at him.

“You heard me. You’ve been going on and on about staking land and building a cabin since you were a kid; well here’s your chance. You’re not gonna find a better spot than this. Get to work.”

‘Unbelievable,‘ I thought, ‘Marching orders from a horse.’ I started to laugh and, with head a-bobbin’ and lips a-flappin’, Andy joined in.

•••

I have the mind of a gerbil. It scampers here, it scampers there. It’s just as happy running on a wheel as anywhere else. Lucky for me, every major decision I’ve had to make roosted in my gut before it registered in my head – a good thing too, because ‘thinking things through’ is hard work for the average gerbil. It also tends to eliminate the passion component.

No thinking was necessary that day on Jamie’s back porch. The decision had already been made. One way or another, I was moving lock, stock and barrel to Atlin B.C. And that was that.