THE DIMINISHED 7th CHORD

One of the chords that comes up consistently in Jazz Standard harmony is the Diminished 7th. Many of the tunes we play from the early American Song Book contain the Diminished 7th chord or are reharmonized versions of those tunes.

Although the Diminished 7th chord shows up as the chord built on the raised 7th degree of the Harmonic Minor, its ‘symmetric’ characteristics come more from the ‘Tempered ‘music system than the ‘Just’ musical system. (Look ‘em up! It’s a great and useful study and it’ll change your ears!)

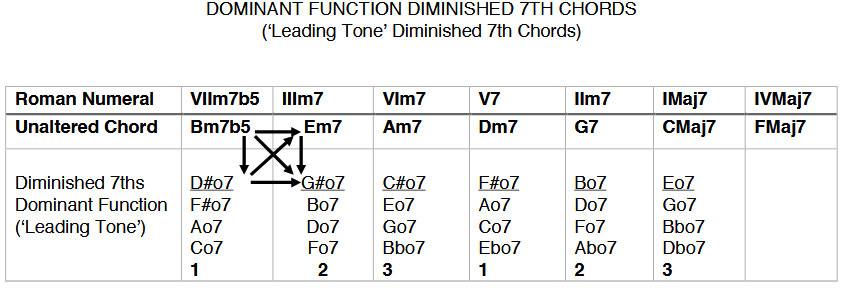

The Diminished 7th chord consists of stacked minor thirds, contains two tritones and has eight well defined resolutions – four with a Dominant function and four with a Subdominant function. The fact is though, the damn thing can resolve almost anywhere, including to other Diminished Sevenths. This makes it a perfect ‘pivot chord’ capable of resolving to key areas near and far. Because we are looking at chord progression within the Major Key for now, though, we’ll look only at Diminished 7ths relevant to the key.

Because of its many functions, the classical terminology that has followed this around has been often complicated and cumbersome. Jazzbos dealing with chord symbols just generally want to get on with the job, so they tend to distill the whole business down to the three simple possibilities for the chord and proceed to name the Root according to the whatever note is the lowest at the time – all voicings being inversions of each another anyway.

So a Bo7 can also be a Do7, Fo7 or G#/Abo7, and to hell with its classical origin. For that reason, simply consider the chords in each category below (1, 2 or 3) to be inversions of each other and feel free name them according to how the bass notes appear in the piece.

That being said, we need to take the time to define the difference between Diminished 7th chords with a Dominant Function and those with a Subdominant Function.

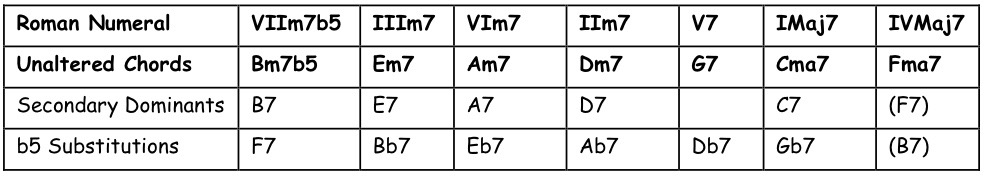

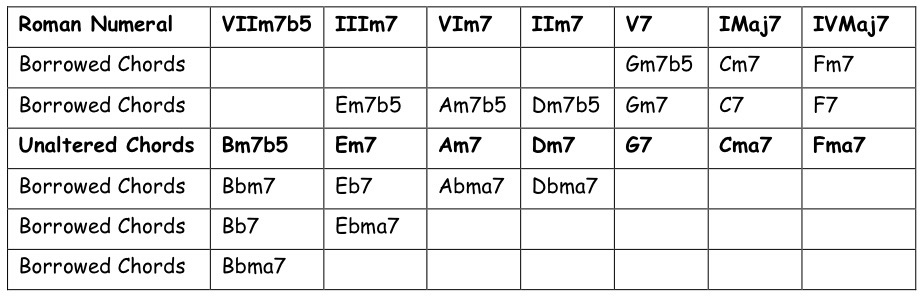

Those with a Dominant Function can be seen below. They are often called ‘Leading Tone Diminished 7ths’ because they lie a half-step below their resolution chord. They lie rather nicely in the cycle of 5ths boxes as follows:

The underlined inversion is the one with the Leading Tone in the bass and is the most characteristic of this movement. All of the other inversions are, of course, available. They will, however resolve to the other inversions of their target chord e.g., in the third to last column:

Do7 – C or C/E; Fo7 – C/E; Abo7 – C/G.

(Note: A Dominant Function Diminished 7th chord can be interpreted as a 7(b9) without its ‘acoustic’ Root. It is sometimes called a ‘assumed Root 7th for that reason, e.g. a Bo7 can be looked at as a G7(b9) without its Root.)

Move through this cycle just like before but note that the movement ‘up’ (e.g.: C#o7 to Am7) is not included. This is, in fact, a Subdominant function. We will look at it shortly.

COMMON USAGE

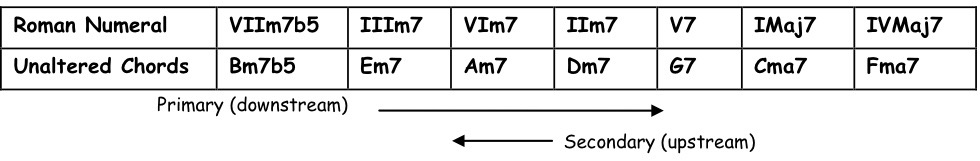

Before we go any further, let’s take a look at SCALEWISE PROGRESSION in the key. Chords tend to flow freely along the Key Scale, e.g.:

Ascending: | C | Dm7 | Em7 | Fmaj7 | G7 | Am7 | Bm7(b5) | Cmaj7 |

Now consider the following:

| Bo7 C | C#o7 Dm7 | D#o7 Em7 | Fo7* Fmaj7 | F#o7 G7 | G#o7 Am7 | A#o7 Bm7(b5) | Co7* Cmaj7 |

With the exception of the Fo7 and Co7, ALL of these Diminished 7th Chords are Leading Tone Diminished 7ths. They are simply the chords in the Cycle of 5ths table in inversions that allow them to double as ascending Passing Chords. This is very common usage.

So what are the Fo7 and Co7 if not Leading Tone Diminished 7ths then?

SUBDOMINANT FUNCTION DIMINISHED 7TH CHORDS

Dominant Function chords are ‘active’ resolving chords … (“Shave and a Haircut … Two Bits!”) Both the Fo7 and Co7 here are Subdominant Function Diminished 7ths.

Subdominant Function chords are ‘passive’ and have a ‘falling back’ character, (“Amen”). As a result, they don’t fit conveniently in the constantly resolving cycle of 5ths table we have created.

One of their functions is to act as ‘Delayed Resolutions’ to, or ‘Elaborations’ of certain chords. Often called ‘Common Tone Diminished 7ths,’ they act very much like a Pedal 6/4 in Classical terminology, i.e. C – F/C – C. Some examples:

| C Co7 | C | | F Fo7 | F | | G7 Go7 | G7 |

| Dm7 G7 | Co7 C | | Gm7 C7 | Fo7 F | | Dm7 Go7 | G7 |

They also function very well as descending Passing Chords, e.g.

| FMaj7 Fo7 | Em7 Ebo7 | Dm7 G7 | C |

Again, all inversions are available. They will, of course, resolve to the other inversions of their target chord.